Eight months ago, I realized that my fledgling climbing career may be coming to a halt in the near future. Adult life doesn’t allow for enormous climbing trips as does a college graduate’s final summer. With that in mind, I set my sights on a goal: to climb the country’s biggest wall, El Capitan, via a route called “the best rock climb in the world:” The Nose. I had never climbed a big wall before. I could count my career trad leads on one hand. But I knew that my personality is a bit obsessive, and that if I wanted this badly enough, it could happen.

I got John Elam on board. Then came Voss. Matt wanted in, but I was concerned: could we climb as four? Inexperience was already stacking the deck against our potential success, and now we’d have an awkwardly large and unorthodox team to further complicate things. But Matt was good, so he joined. I started a thread on Mountain Project: “Speed Big Walling as Four.” I asked if this could be done. Overwhelmingly, the response was “no.”

Well, despite these roadblocks, I can confirm that, two weeks ago, the four of us topped out a three-day (well, three-and-a-half-day) ascent of the Nose with plenty of daylight to spare. I don’t say that as a big “told ya so” to the many reasonable people who thought it couldn’t be done. I do say it to encourage folks who want to go big and/or climb with a large team to go for it! If you do you homework, dial in your systems, and can find it within yourself to muster three days of extraordinary mental stamina, you can climb El Cap. Here’s how we did it:

After a 7AM start, we had camp packed up and Elam and I were blazing down Tioga Pass into the Valley. He and I were going to fix line up the route’s first four pitches, stopping at Sickle Ledge. Contrary to the typically casual feel of line-fixing days, Sickle was just under 600 feet off the deck and would require a considerable amount of tricky aid. Many call the four pitches to Sickle the hardest on the entire route in terms of aid placement trickery. Needless to say, Elam had his work cut out for him. Our goal was to be done be 3PM, at which point Matt and Voss would haul our heavier-than-ever haul bag up the fixed lines.

We rolled into the El Cap Meadow parking area around 8:30 and began racking up. Elam was bringing the aid rack and a small hydration pack; I was carrying a sizable backpack stuffed with four ropes, three for fixing rappel lines plus our thin tag line for pulling up gear. The approach was heinous–oh wait, it was actually incredibly easy and took five minutes. It’s almost comical that the biggest big wall in the country is not in some remote alpine environment, but five minutes but a parking spot in a balmy valley setting. Either way, I wasn’t complaining as we began to flake out our lead line at the base of the Big Stone. Side note: my goodness, El Capitan is huge. “Words can’t explain” doesn’t help, so I’ll just say hat if you’re ever near the Valley, stop by and walk to the base.

There are only “four” pitches to get to Sickle Ledge, but there is technically a “Pitch Zero” to get to the first pitch. There are two options for “Pitch Zero:” an easy 5.7 called “Pine Line” or a 4th-class scramble just to the right that travels up easy but exposed terrain. Since we weren’t hauling until the lines were fixed (Pine Line is easier for hauling) we took a right at the fork in the trail to head to the 4th class…or so we thought. In fact, both the Pine Line and 4th class starts require taking a left at the fork, which meant that our chosen start route was something completely off route. Elam began leading. He reached a platform with two fixed pitons, which he clipped. He eyed the section above. “This is not 4th class terrain,” he concluded, at which point I reassured him that he would be able to go on somehow. He pulled a tricky mantle move, only to find an unprotectable section of funky friction climbing with no holds. “Where do I go?” he asked. Slowly, he pushed onward, growing increasingly disturbed at the distance between himself and his last piece of protection. He climbed out of sight. Two hours after we had begun, I heard those words of relief: “Take me off belay!”

The mystery pitch of horror was a very runout scare-fest of 5.9-ish climbing, eventually meeting up with the two established lines to the base of the route. Because the climbing was so sketchy, however, Elam had to travel carefully and avoid getting further off route. Down-climbing wasn’t really an option, so he had to be cautious to go the right way. Especially frustrating was the moment when he saw the 4th class section, which may have taken five minutes at most to climb.

Despite being behind schedule, Elam didn’t waste any time hopping on the best rock climb in the world. The pitches to Sickle are not too memorable except for their tricky aid, which is a good description of the rest of that day. The most challenging pitches had some fixed gear, which sped things up a bit, but most of the leading was a bit of a grunt. We got to the top by about 4:30, where to our dismay we encountered a 3-man team of Korean climbers. Concerned that we would get stuck behind them, we asked what their plans were. We were incredibly relieved to find out that they were doing a 5-day ascent, and that they were taking a rest day before returning to their lines. This seemed like a strange strategy to me (fixed lines are never supposed to be up for more than 24 hours, but they may not have known this), but I wasn’t going to complain. We fixed lines and rapped 600 feet to the Valley floor, where Matt and Voss spent the evening hauling our own 150-pound goodie bag to the ledge above. Watching the pig lift off the ground was a big relief, as we were unsure of the difficulty of hauling such a heavy bag. After a good show of watching the hauling from below, the four of us reunited and drove to El Portal for dinner and sleep.

5AM. Matt and I were teaming up to lead the first two blocks, so we jumped immediately into the car and bee-lined for El Cap Meadow. We were back on Sickle Ledge by 6:30 and leading by 7. Thirty feet into his first pitch, Matt shouted down those words that a belayer never wants to hear: “I need to poop!” I haven’t mentioned this piece of big-wall logistics before, but any multi-day objective requires a poop tube, a odor-proof tube filled with plastic bags in which climbers do their business. Generally, this is a slightly gross reality that isn’t too difficult to handle. Nobody had yet used it on the middle of an aid lead, however! Matt pulled up his tag line, poop tube in tow. Some five minutes later, the deed was done when, all of a sudden, I realized that I too needed to participate in the sacred toilet ritual. This inconvenient and surreal poop train set us back ten minutes, but soon we were back on track with Matt cruising his way up to Dolt Hole.

Dolt Hole is a section of wide crack climbing that emerges into a brief but tricky chimney, of which Matt dispatched quickly. In the following stretch of easy aiding, however, I suddenly heard a loud PING! and immediately braced for the sharp tug of catching a lead fall. It never came, and I looked up to see that Matt had fallen some 10 feet and was hanging upside down from something, stunned and justifiably spooked. He carefully inverted himself and discovered, to his horror, that a carabiner had accidentally cross-loaded and the wire gate had snapped open, dropping him what would have been some 30 feet–except his foot had somehow caught an aid ladder loop and arrested his fall! Matt, who suffers from a history of concussions, had just missed whacking his helmet on a rock and was obviously relieved to have so narrowly avoided potential injury. It’s one of those one-in-a-thousand incidents that you just have to shake off.

Shake it off he did, as Matt reached the top of his pitch and began lowering off into a big pendulum move, in which the leader runs back and forth along the rock in an attempt to swing into a neighboring crack system–in this case, the Stovelegs. The Stovelegs are a crack system stretching hundreds of feet straight upwards, spanning about two inches wide for most of the distance. This size crack is a free climber’s dream, as it allows for your entire hand to sink into the crack and then easily hold tight in place with tremendous security. When Warren Harding initially ascended the Nose, this wider section could only be protected with a wide chock of some sort; Harding used sawed-off metal stove legs, hence the name.

After sticking the big pendulum swing, Matt began jamming his paws in, one after the other, making his way up to his pendulum point some 15 feet to the left. If he had fallen, he would have violently swung leftward, but he seemed confident in the climbing and continued upward. After a while, he switched to aiding, leapfrogging cams over and over again for hundreds of feet. Exhausted, Matt finally reached the end of the Stovelegs and pulled up onto Dolt Tower. I took over the lead and led three more easy pitches to our night’s bivy spot: El Cap Tower. The bivy was nice and comfortable, and with no other parties on the other route, we couldn’t have asked for a better start. We made it to our destination with plenty of daylight left, but the toughest day lay still before us. With that, we ate dinner and went to sleep.

5AM, day two. It was my turn to lead. My block was an enormous sequence of back-to-back classic pitches, and I was incredibly excited. First up was the Texas Flake, a gargantuan, Texas-shaped slab of rock hanging improbably off the wall as if it could peel off at any second. Between the backside of the flake and the wall is a large chimney slot that the leader must ascend via free climbing (no piece of protection is large enough to aid the pitch). This wouldn’t be a huge problem (the pitch goes at the comfortably moderate grade of 5.8) except that there is no protection for 25 feet, at which point there is one bolt, then 25 more feet to the anchors. The wager increases all the more when you consider that the easiest way up is fifteen feet left of the mid-way bolt. What do you do? Do you pick the easier climbing with no protection for 50 feet, or the harder climbing with no protection for 25? After considering the options, I realized that I shouldn’t be falling on 5.8 either way, and I decided to remove my 30-pound rack of gear entirely from my body and take only a single, lightweight quickdraw. Feeling light as a feather, I decided to take the easier, but scarier way and pass up the bolt. It wasn’t nearly as bad as I had expected, and I moved quickly up the chimney to the anchors.

From the top of the Texas Flake, it was a quick bolt ladder up and left into some tricky aid. I got to use a cam hook for the first time, which was cool. A cam hook is literally a bent piece of metal that twists into a cammed position as you weight it. As soon as you unweight it, it falls out. The mantra that I had always heard with cam hooks was “they just work.” It’s true! I felt sure that it would pop out of the thin crack at any second, but I guess not. From there, I climbed into the Boot Flake crack. Boot Flake is one of El Capitan’s most recognizable features, as it simply a large, boot-shaped flake of very light rock right in the middle of the Big Stone. Most folks would at least consider free-climbing such a classic pitch, but I’m garbage at climbing so I just aided as quickly as possible.

With the Boot dispatched, it was time for the climactic moment of my entire climbing career: the King Swing. Out of everything I have ever done in rock climbing (which, admittedly, isn’t too much), nothing compares to the thought of sprinting back and forth across blank rock with thousands of feet of air beneath you, desperately trying to make it to the crack system 40 feet to the left. For some reason, I was so worried about the Texas Flake that, having completed it without incident, I reckoned that the King Swing would prove to be an enjoyable, low-exertion, high-fun endeavor. So you can imagine my disappointment when, after grabbing hold of a tiny edge after my first desperate swing, I realized that I was nowhere near my destination (a small ledge called Eagle Ledge). No, I had to swing some ten feet further, around a corner, to some supposed blind handhold that seemed impossible to reach. After ten or so attempts, I heard the shouts of onlookers down in El Cap Meadow egging me on with loud monkey noises (reminiscent of the infamous Stone Monkeys era of Yosemite climbing typified by the likes of the late Dean Potter). Little did they know, my love language is loud monkey noises of affirmation, so with renewed confidence I pushed on with another slew of attempts. I stuck the hold, but without the momentum needed to pull myself around the corner to Eagle Ledge. The monkey noises got louder, but I had to let go and swing all the way back to Boot Flake. And then, after a few more tries, I got it. I stuck the hold, and with everything I had I mantled over the corner. Slowly, I tensioned over to Eagle Ledge, and then it was finished. I screamed with joy as monkey sounds filled my ears from 1500 feet below me. I will hopefully never type that combination of words again.

The rest of my block was rather uneventful from my perspective, although we got a rope improbably stuck on a lower-out sequence, which burned an hour of time. Behind schedule and dog-tired, I reached Camp IV and handed the lead over to Voss.

Voss had a 7-pitch marathon block filled with some tricky aid pitches, which is a thing that approximately 7 people in the world like to climb. Luckily, Voss was one of them, and he blasted off into the Great Roof ready to have fun. The Great Roof is a stunning line, a clean, right, leaning arch with an enormous ceiling jutting out over our heads. The heat, nearly unbearable by this point, quickly gave way to the shade as Voss clipped his way into the traversing section. To his good fortune, the roof crack was littered with tiny fixed nuts, meaning that he didn’t have to place too much thin gear himself. He dispatched the Great Roof without incident, ready for the next pitch.

Immediately following the hyper-technical, insanely strenuous (free) climbing of the Great Roof, you wouldn’t expect there to be a 5.10a lieback flake up huge holds for a hundred feet. And yet, the Pancake Flake remains one of the most classic free climbing pitches of the Nose. Naturally, we gave it to a man whose mantra is “literally, why would anybody ever free climb, ever?” Though willing to attempt a free climbing strategy, when a dehydrated Voss saw that the pitch’s bolts had been chopped by a bolting ethics vigilante, he opted to aid the pitch instead. His one condition was that we never tell anybody that he aided the Pancake Flake, since that would be a career-endingly embarrassing fact to admit. Hilariously, some thirty feet into the lead, Voss took a big fall on his self-belay device. I looked up, baffled at what could have happened on such an easy pitch. “The flake broke!” shouted Voss. “If this happens again, I will have seriously altered the appearance of the route for all eternity.” Luckily, it didn’t happen, and he finished the pitch.

The rest of Voss’ block was a hodgepodge of tricky aid and easy free climbing, mostly without any trouble. In particular, the Pitch Beneath the Glowering Spot proved very strenuous and thin, and the Camp 5 pitch was a bit scary coming off the deck. In general, however, the end of the day was just an absolute grind. The light began to fade as we neared Camp VI, our night’s destination. Voss hadn’t had a sip of water in hours, and the heat was barely bearable even out of the harsh sun. The haulers seemed to be moving well, but they too were tired. As Voss mantled up onto Camp VI and fixed my lines, night was just setting in and we were dogged. I joined Voss and saw that our camp was a mixture of little space, lots of stuff and disgusting smells emanating from a deep chasm filled with trash from previous parties. Barely able to think about anything but water, Voss sipped what was left from my hydration pack and we waited for the haulers.

When Elam topped out, he realized that, in an effort to hurry, he had forgotten the haul pulley. Livid, Elam had hit a breaking point of stress. At this time, it became clear that being on a wall for this long is grueling business–physically, sure, but mostly in terms of the mental battle. Cabin fever, endless small mishaps and frustrations between team-mates have a real and cumulative effect on morale. Out of the whole trip, this was the low point for our team’s morale. Elam yelled down for the pulley, and disagreement emerged as to how best retrieve it. After resolving the issue, the bag lurched up over the edge with Matt following soon behind. Emotions ran high and all of us got in a heated exchange about every little thing that had gone wrong that day. After a while, the anger subsided and became a pragmatic truce, as we realized that dinner and sleep were the priority, not arguing out our differences. Few words were said that night as we set up a portaledge and tried to squeeze four men into a bivy for two.

The next morning, we woke up feeling much better than expected. Everybody talked through the previous night’s altercation and we re-focused on our goal: knocking out the final six pitches. Elam took over the lead for the hardest free-climbing pitch on the route: Changing Corners. It follows a comfortable crack for some thirty feet, at which point the leader must transition into another, super-thin corner eight feet to the right. Separating the two corners is an arête, or outward-facing corner, with no handholds. In the 90s, when Lynn Hill made the first free ascent of the Nose, and everything came down to this pitch, a savagely difficult 5.14a with the crux at the “corner change” sequence. Elam, of course, is not a 5.14 climber, and so he aided the pitch. Nonetheless, the pendulum through the “changing corners” bit proved tricky and challenging from a rope management standpoint. As he executed the pendulum, we heard Elam shout in amazement, “Wow, Lynn. This is incredible.” And incredible it was.

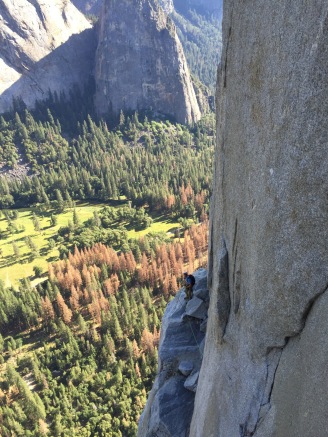

After Changing Corners, two more moderate pitches placed us at our final belay changeover, the “Wild Stance.” Voss and I were hauling a now-much-lighter bag up to the stance, having a grand old time. Spirits were high, and they perked up even more as we ascended our rope up to the stance, which truly was “Wild.” After many pitches in the shade, feeling rather enclosed in corners, you suddenly emerge into the full sun with an enormous, overhanging pitch above and a view of the entire route below. “Big air” is an understatement.

Matt took the lead for the final block, a not-too-challenging bolt ladder up through the final headwall, mixed with some easier free climbing. These pitches may have seemed less-than-noteworthy compared to the rest of the route, but on Warren Harding’s first ascent, they were some of the most amazing. Harding, after over a year working on the route, had committed to a ground-up ascent to finish the thing once and for all. It took him seven days to get to our position when a three-day storm rolled in. After it cleared, Harding pushed to the top by hand drilling and placing 28 expansion bolts. If you’ve never hand drilled a slab of granite, it takes a half an hour or so per bolt. Harding worked some 15 hours through the night before topping out at 6AM, in one of the most stunning achievements in hardman-ery to date. As Matt clipped his way up these bolts, he was following the same path that Harding had drilled in 1958, albeit with considerably less effort. After a good wait at the Wild Stance, we finally heard Matt shout “Lines fixed!” meaning that we could blast off.

Jugging up the headwall will remain one of the most stunning memories of the ascent. You feel like an astronaut, floating in space with no ability to control your rotation; except instead of space, you’re in beautiful Yosemite Valley some 3,000 feet off the ground. As I scanned the horizon, I could see all of our previous ascents: Leaning Tower, Higher Cathedral Rock, El Cap’s East Buttress, Washington Column (okay, you couldn’t actually see Washington Column), Manure Pile Buttress, and Half Dome looming in the distance. I realized that each of these climbs had slowly prepared us to be where we were: about to top out a three-day of the Nose with plenty of light to spare. I felt profoundly aware of our good fortune in being able to acquire our gear, take a month off of life, and get so much help along the way to make this possible. It was a blessing, not merely an achievement.

I pulled up over the lip of the headwall and caught eyes of the summit. Matt had already reached the top (before 4PM!) and was fixing a hand line up the 4th class near the descent trail. We slowly worked our way, one by one, up the final pitch along with all our gear, and then we were there: the summit tree. Water was consumed. FaceTimes were made. Loved ones breathed a sigh of relief. We’d done it!

Our descent down the East Ledge was a bit tricky with heavy bags, but we’d done most of it before on our East Buttress Ascent (I’d HIGHLY recommend familiarizing yourself with this descent before attempting one of the Grade VI lines). Ironically, Matt tripped while walking down the trail and badly cut his wrist on a rock, which was the worst injury sustained in our entire month in the Valley. We made it to the car just before 7PM, and took a dip in the Merced. The frigid water was glorious. We met up with some friends (they were hiking the John Muir Trail) for pizza and sprayed about all our incredibly brave and valorous achievements.

And then it was finished. A month in Yosemite, four walls, and some other stuff. I was stunned at the sense of closure this experience gave me. After agonizing over every detail of this trip and the training regimen involved, I honestly felt that I could quit climbing now and live a happy life. It’s a sort of peace that makes you truly, fully happy. For many, the Nose is easy. Alex Honnold and Hans Florine climbed the whole route in under two and a half hours. But for me, this was a good capstone to an activity that I love. The other guys seemed similarly filled by the whole experience, but I’ll leave them to share their own sentiments of what lies ahead. In the meantime, I’m going to get some rest.

Wow Beautiful story.

I like how you called the whole experience “More a blessing than an achievement.”

That’s how I feel about my few climbing adventures too.

May God continue to bless you with life and the love of family and friends.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person